Eating Air (1999) Jiak Hong / 吃風

13/10/2010 Leave a comment

Country: Singapore

Country: Singapore

Language: English, Mandarin, Hokkien

Director: Kelvin Tong & Jasmine Ng

Runtime: 100 minutes

Starring: Benjamin Heng, Alvina Toh, Joseph Cheong, Mark Lee, Michelle Chong

Theme: Crime/Gangsterism

Ratings: IMDB: 4.9/10

Film Festivals:

2000 Rotterdam International Film Festival (RIFF)

2000 Singapore International Film Festival (SIFF)

2000 Stockholm Film Festival (SFF)

Awards:

2000 Silver Screen Award for Young Cinema (SIFF) – Kelvin Tong, Jasmine Ng

2000 FIPRESCI Prize – Honorable Mention (SFF), “for its sense of escapism and youthful dreams through visual metaphors, special effects and inventive humour.”

Nominated:

2000 Tiger Award (RIFF)

2000 Silver Screen Award for Best Asian Feature (SIFF)

2000 Bronze Horse (SFF)

Eating Air is former film critic Kelvin Tong’s debut feature film foray, albeit a joint collaboration with another directorial upstart Jasmine Ng. It remain the latter’s sole feature film work, having went on to documentary direction with credits in Lonely Planet Six Degrees and Invisible City. Kelvin Tong, however, boasts subsequent box office hits like The Maid (2005), Rule No 1 (2008) and Kidnapper (2010) to his filmography. It must be noted that Eating Air was one of the films to premiere amongst the influx that came with the renaissance of Singapore cinema, and it was also one of the many that fell flat, failing to break even. Made on a budget of S$800,000, it only managed to gross $350,000 during its month-long run.

A significant feature of Eating Air is its heavy use of visual metaphors and special effects, a tone set right from the start through the use of bright, sharp, vivid colors throughout the film that sometimes border on psychedelic. The punk, proletariat tone of the film is set right from the start through the use of stereotypical clichés. First, we have Ah Boy (the protagonist) on a motorcycle spinning left and right (despite keeping within his lane) along the virtually deserted roads along Bugis. The punk rock track in the background lends credence to this mood in the opening sequence. We then see Ah Boy entering the expressway when another motorcycle pulls up beside him. The symbolic act of sharing a smoke cements their relationship as good friends. The scene ends with another car with troublemakers chasing them, which eventually gets into a chain collision, the comedic tone set when the hooligans get out of the car ready to start a brawl and they realize their motorcycles simply would not start; they then sit by the kerb, bloodied (03:21).

Further establishing the uncouth nature of the movie is Ah Boy’s first actions after waking up from bed. Topless, he stretches as he stands by the doorway and gives his crotch a gentle scratch (04:25).

Further establishing the uncouth nature of the movie is Ah Boy’s first actions after waking up from bed. Topless, he stretches as he stands by the doorway and gives his crotch a gentle scratch (04:25).

Chinese/Japanese martial art comic impressions (04:19) are visible through Ah Boy’s surrealist dream sequences that start off with a clap of thunder in the background and him wielding a sword to fight with a ninja (04:12). Such instances are peppered throughout the film, and his opponents range from his parents (04:50), geishas (26:51) and even the elevator (06:09). “In this world, I walk alone,” he declares.

Chinese/Japanese martial art comic impressions (04:19) are visible through Ah Boy’s surrealist dream sequences that start off with a clap of thunder in the background and him wielding a sword to fight with a ninja (04:12). Such instances are peppered throughout the film, and his opponents range from his parents (04:50), geishas (26:51) and even the elevator (06:09). “In this world, I walk alone,” he declares.

A key scene (and a very clever one, I must add, in terms of aesthetics and technique that all film students really should study) of the movie begins in the photocopying shop at 27:34, which captures the menial, repetitive nature of the job. The rhythmic scans of the machine is remixed with steady drum beats, marking the begin of a full two-minute long sequence that leads to other rhythmic actions. We see Ah Girl playing with her purple pen, a man walking by the shop, a lady ironing clothes, a man playing with coins, a man swinging the plastic bag, an athlete bouncing a ball, a man lifting weights, a hostess banging on her mike etc. This smooth rhythm creates a prominence of menial Singaporean tasks that many have taken for granted and not paid much attention to. Further, it bears a stark contrast to the gang chase that ensues.

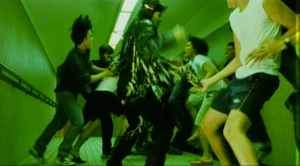

The anime influence of the movie is further expounded through the emphasis on the blow of punches and faces hitting the wall, through close-up shots utilized at 30:40 for instance. Further, the anime emphasis on color is evident in the scene at 35:30, where a black-white, good-evil dichotomy is omnipresent through their attire. This scene is further contrasted with

The main difference between Eating Air and Royston Tan’s seminal 15 (2003) – which also deals with similar themes of gangsterism – is that the latter came under heavy scrutiny by the film censors, and thus was thrusted into the public limelight. Eating Air perhaps failed on this count, aside from its poor timing that pushed it into the shadows of other more prominent commercial releases such as Jack Neo’s Liang Po Po: The Movie (1999) and the Fann Wong-helmed The Truth About Jane & Sam (2000). While it did make a slight ripple on the international film festival circuit for its vivid tones and inventive humour, I believe this remains one of the most underrated Singaporean films of all time. For it manages to capture the root and essence of the Singaporean culture (the next film that manages to do that, in my opinion, is Singapore Dreaming (2006)), whilst seamlessly marrying elements of Japanese manga anime within.